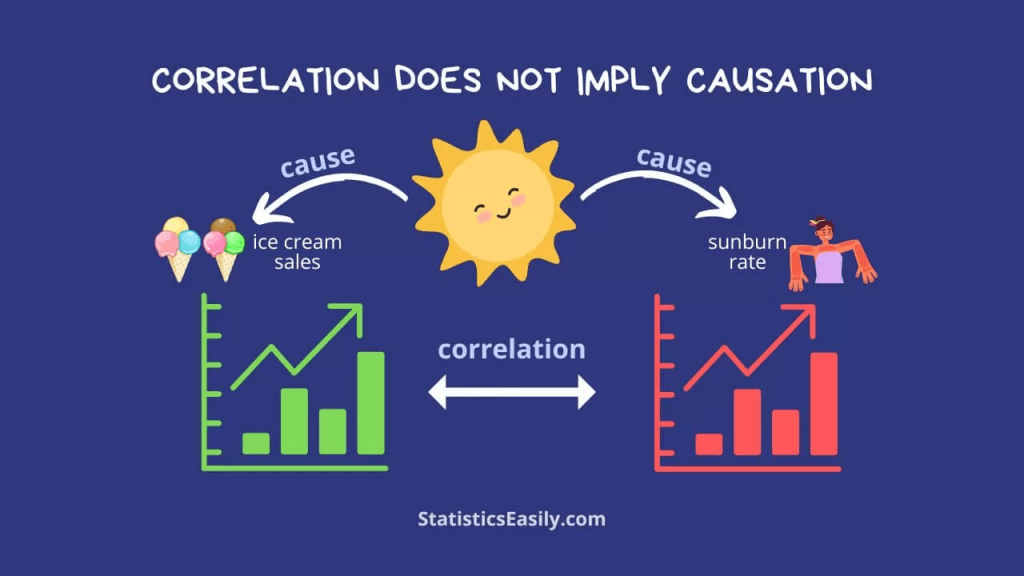

This week The Independent went with a headline declaring that AI chatbots are “pushing people towards mania, psychosis and death – and OpenAI doesn’t know how to stop it.” It’s dramatic, designed to shock. But it misses the point that while AI has tremendous potential to cause harm, correlation is not causation, nor is the linkage being made here recognizant of the fact that most AI models are derived from engagement with various sources. Simply put, the quality is only as good as what is put in. Blaming models for not making significant assumptive leaps is not helpful, but there are factors to be considered for the future of AI recognition of suicidality, potential action, and response.

“ChatGPT is pushing people towards mania, psychosis and death – and OpenAI doesn’t know how to stop it.”

The piece opens with a series of unsettling anecdotes, cases where people in distress allegedly found their mental health deteriorating after prolonged use of ChatGPT. Some slipped into manic spirals, others became more deeply enmeshed in psychotic thinking, and a few were described as moving closer to suicidal action. Experts quoted in the article reinforced these worries. Psychiatrists and ethicists warned that AI’s conversational style can mirror the racing associations of mania or reinforce delusional systems, sometimes without challenge. Because ChatGPT responds in a human-like manner, users may anthropomorphise it, imagining a companion or confidant where none exists. For vulnerable people, that can blur lines between imagination and reality in ways that worsen their state.

The article stressed that ChatGPT’s risks are not only about direct harm but about amplification. While Google search is impersonal, ChatGPT talks back, often with warmth or apparent empathy. That interaction can deepen unhealthy reliance and feed into distorted thinking. Safeguards exist, but they tend to catch only the most obvious red flags — direct mentions of suicide or self-harm — while missing the more subtle cues that often mark the early stages of crisis. OpenAI, according to the piece, admits it does not yet have a full solution. Its moderation systems are evolving, but the company struggles with the sheer complexity of detecting mental health risks in real time. For now, there is no comprehensive safety net.

The overall tone of the article is cautionary, almost alarmist. It frames ChatGPT as a system capable of “pushing” people toward extreme states and even death, though the evidence rests mainly on anecdote and expert speculation rather than systematic data. The effect is to cast generative AI not as a neutral tool but as an active risk in the mental health landscape, with OpenAI portrayed as a company racing to plug holes in a system it may not fully understand.

Tools Don’t Cause Suicidality

Let’s be clear: blaming a chatbot for suicide is like blaming Google for showing directions to the nearest bridge, or blaming a pen for writing a suicide note. The tool mediates; it does not originate. Suicide is not born in silicon, it is born in human pain, social isolation, and systemic failure. When someone is spiralling, they might bring that spiral anywhere — into Google, into ChatGPT, into a notebook, or into a late-night conversation with a stranger. The medium absorbs the energy of that moment, but it does not create it. What the technology does is reflect it back. Sometimes it reflects awkwardly, clumsily, or even unhelpfully, but reflection is not causation. The risk is not that AI manufactures despair out of nothing. The risk is that it mirrors despair too literally, or amplifies the speed and intensity of thought when someone is already vulnerable. That can feel like acceleration, but it is not ignition. Just as a mirror in a dark room does not invent the darkness, AI does not invent suicidality. It reveals it, refracts it, sometimes throws it back in ways that sting. This distinction matters, because if we pin the cause on the machine, we let ourselves off the hook. We ignore the fact that suicide arises in the crushing weight of lost work, fractured relationships, untreated illness, stigma, silence. We ignore the emptiness of our mental health systems, the patchwork of occupational health, the loneliness of those reaching for anything — even a chatbot — because nothing else is there. So yes, technology reflects. And reflections can be dangerous when you are already unsteady. But the real danger is pretending the mirror is to blame for what it shows.

The Reflection Problem

This is the bit that matters. AI doesn’t invent mania, or psychosis, or suicidal thoughts. What it does is mirror. Like a pane of glass, it throws back what is already there, sometimes distorted, sometimes exaggerated, but always derivative. If someone types in fast, pressured, disjointed bursts — the sort of racing speech that clinicians instantly recognise — the model will often respond in kind. It’s not “deciding” to be manic; it’s pattern-matching the input and reflecting its tempo. If someone frames a question in terms of self-harm, the model may echo the phrasing, simply because it has been trained to reflect back the shapes of human conversation. That reflection can act like an amplifier, making what is already loud inside the mind sound even louder on the page. This is not creation. It’s repetition with volume turned up. AI doesn’t generate the underlying state; it mirrors the behaviour and tone that signal it. But mirrors can be treacherous. Look into one long enough, especially in a moment of crisis, and you can mistake the reflection for confirmation, even encouragement. The danger isn’t that ChatGPT plants new ideas. It’s that it risks reinforcing the ones already circling in someone’s head. For a person in distress, seeing their fragmented or hopeless language echoed back can feel like validation: “Even the machine agrees.” That is not therapy, and it is not support — it is mimicry mistaken for meaning. And that is why mirrors matter. When you don’t realise you are looking at one, you may believe you’re seeing truth rather than reflection. In the context of suicidality or psychosis, that confusion can deepen the spiral. AI isn’t the origin of the storm, but it can bounce the lightning around until the room feels brighter, faster, harder to escape.

The “Casual Leap”

The article seemed to suggest AI should jump from: “I’ve lost my job” → “this person is suicidal.” But no machine — and no person — can safely make that leap every time. Sometimes job loss is just job loss. Sometimes it’s grief, sometimes it’s frustration, sometimes it’s a life-changing crisis. Context is everything, and context is exactly what a chatbot cannot reliably hold. Even trained clinicians tread carefully here. They don’t leap from one disclosure to a definitive conclusion — they ask, they explore, they sit with the uncertainty. To expect an algorithm to make that judgement instantly is not just naïve, it’s unsafe. At best, it leads to false alarms that erode trust and frustrate users. At worst, it normalises the idea that anyone expressing difficulty at work is a suicide risk — which is neither clinically sound nor socially responsible. AI is not a mind reader. It doesn’t know the history behind the words, the tone of voice, the silence between sentences. It only has the text. To project psychiatric omniscience onto it is dangerous wishful thinking. And the irony is, if companies train AI to assume “distress equals suicidality” every time, we risk blunting the moments when genuine suicidal intent does surface — because everything gets flattened into the same automated crisis script. The leap from job loss to suicide cannot be automated. It requires human judgement, human listening, and human presence. Asking a machine to carry that weight is like asking a mirror to tell you if your bones are broken. It can only show you the surface.

What AI Companies Should Own

That said, AI isn’t absolved. Poor design can and does cause problems. Chatbots sometimes reinforce delusion by playing along with distorted thinking, they can mirror the pressured rhythms of mania, and they can answer dangerous queries far too literally. That doesn’t make AI the cause of a death, but it does make it an avoidable risk magnifier. A badly placed mirror doesn’t invent the storm, but it can throw the lightning back into your eyes. I know this first-hand. The version of AI I work with has been tuned — painstakingly — to respond with caution, sensitivity, and care whenever suicidality is raised. It doesn’t dismiss, it doesn’t sensationalise, it doesn’t panic. It reflects responsibly. But that’s not what most people get when they open a free chatbot window. They get the off-the-shelf model: patchy, inconsistent, sometimes clumsy, and rarely attuned to the nuances of context. And in a crisis, that gap matters. The difference between “I hear you, you’re not alone, here are some supports” and “I cannot help with that” isn’t cosmetic. It’s the difference between being met with a bridge and being met with a wall. For someone already on the edge, a wall can feel like confirmation of silence, abandonment, or hopelessness.

AI may not be the cause, but design determines whether it functions as a safe mirror or a distorting one. That is where responsibility lies.

The Real “Scandal”

The real scandal isn’t that AI kills people. The concern is that so many people are turning to a chatbot in the first place. They aren’t doing it because they believe a machine is better than a human — they’re doing it because the human response so often isn’t there. Mental health services are overstretched and underfunded. Occupational health is treated as a box to tick, not a lifeline. And when people in acute distress reach out, too often they are met with silence, waiting lists, or indifference. In that void, even a chatbot starts to look like a company. AI didn’t invent that silence. It simply reflects it back to us, uncomfortably, in its cold imitation of care. That should be the focus of the debate. Instead of casting AI as a malevolent therapist, we should be asking: how do we build guardrails so that reflection doesn’t tip into amplification? How do we make it crystal clear that this is not therapy, not a clinician, but a tool? And most importantly, how do we fix the human systems so that people don’t find themselves testing the limits of a chatbot in their darkest moments?

ChatGPT isn’t a grim reaper. It’s a mirror. If we don’t like what we see in the reflection, that says more about our society than about the machine.

Leave a comment