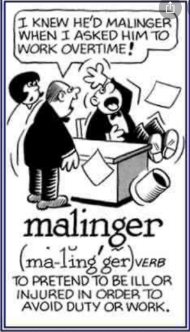

I was recently asked by a valued colleague if within the modern military historic understanding of malingering is still applicable: I argue yes, and that Social Media response turned into this article (again – oops)

In 2003, Staff Sergeant Georg-Andreas Pogany, an interrogator with the U.S. Army’s Green Berets in Iraq, witnessed the gruesome aftermath of an enemy attack. The experience triggered severe panic attacks, and recognizing the symptoms, he sought medical assistance from his superiors. Instead of receiving support, Pogany was charged with cowardice—the first such charge in the U.S. military since the Vietnam War. If convicted, he could have faced the death penalty. The charge was later reduced and eventually dropped, but the damage was done. Pogany’s case became a striking modern example of how seeking medical help—especially for mental health—can be perceived as a failure rather than a necessity in military culture (Borger, 2003).

Modern armies, particularly in the UK and US, maintain strict expectations regarding medical readiness. The focus remains on keeping soldiers operational for as long as possible, often at the cost of their long-term health (Hoge et al., 2004). But within this system, a deeper issue persists: the pressure to endure, to push through pain no matter the consequences. Elite units, such as paratroopers and Special Forces, hold an even greater expectation of resilience. The phrase “pain is temporary” is embedded into the military psyche. Yet, for many, untreated injuries and trauma become lasting wounds, both physically and psychologically (Williamson & Mulhall, 2018).

Military doctors face a difficult task—assessing whether an injury or illness is legitimate while navigating a culture that often dismisses or punishes vulnerability. The consequences of misjudgment are severe. A soldier sent back into combat with an undiagnosed traumatic brain injury (TBI) or severe post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) could become a liability to themselves and their unit (Brenner et al., 2018). At the same time, the fear of being labelled a malingerer prevents many from seeking care, reinforcing a cycle where suffering remains hidden (Greenberg et al., 2017).

Since the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, reports of mental health struggles among NATO forces have increased significantly. However, medical discharge rates remain low, suggesting a continued reluctance to report issues (Iversen et al., 2011). In the UK, programs like Trauma Risk Management (TRiM) aim to normalise mental health discussions within military units, while the US Army has introduced Embedded Behavioral Health teams to integrate mental health support more seamlessly. Despite these efforts, the stigma persists. Soldiers fear a diagnosis could end their careers, prevent promotion, or isolate them from their peers (Jones et al., 2019).

Suicide remains a devastating reality in the UK and US militaries, with many service members who die by suicide never having sought formal mental health support during their careers (Shen-Yi et al., 2018). Some fear the impact on their future, while others are trapped in the same mindset that led Pogany to be accused of cowardice—push through, endure, survive.

The accusation of malingering has long been used to dismiss genuine suffering (Wessely, 2006). While some soldiers may exaggerate minor injuries to delay deployment, the more pressing issue is the opposite—those who underreport pain and psychological distress, fearing professional or personal repercussions. The military culture of resilience, essential in combat, can also become a double-edged sword. Soldiers are trained to fight through hardship, but true strength sometimes lies in recognising when to stop and seek help.

References

- Borger, J. (2003). “US soldier charged with cowardice after panic attack.” The Guardian. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2003/nov/08/iraq.julianborger

- Brenner, L. A., Forster, J. E., & Hostetter, T. A. (2018). “Traumatic Brain Injury, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, and Suicide Risk Among Veterans.” Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 33(4), 232-240.

- Greenberg, N., Langston, V., & Jones, N. (2017). “Trauma Risk Management (TRiM) in the UK Armed Forces.” Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps, 163(2), 90-93.

- Hoge, C. W., Auchterlonie, J. L., & Milliken, C. S. (2004). “Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan.” JAMA, 295(9), 1023-1032.

- Iversen, A. C., van Staden, L., Hughes, J. H., Greenberg, N., Hotopf, M., Rona, R. J., & Wessely, S. (2011). “The stigma of mental health problems and other barriers to care in the UK Armed Forces.” BMC Health Services Research, 11, 31.

- Jones, N., Campion, B., Keeling, M., & Greenberg, N. (2019). “Stigma and barriers to care in service leavers with mental health problems.” Occupational Medicine, 69(2), 81-88.

- Shen-Yi, C., Zhao, X., & Smith, R. (2018). “Suicide among military personnel: A review of risk factors and prevention strategies.” Military Medicine, 183(5-6), e187-e195.

- Walker, S. (2019). “If We Want to Address the Crisis of Veteran Suicide, We Must Acknowledge Its History.”, Time Magazine, Accessible at https://time.com/5670036/veteran-suicide-history/

- Wessely, S. (2006). “Twentieth-century theories on combat motivation and breakdown.” Journal of Contemporary History, 41(2), 269-286.

- Williamson, V., & Mulhall, E. (2018). “After the battle: Exploring military veterans’ experiences of physical injury, PTSD, and medical stigma.” Social Science & Medicine, 207, 67-74.

Leave a comment