By Dr Simon H. Walker

Another “Thanks, but no thanks.”

Promotion rejected. Funding application rejected. Job application rejected — again.

I wish I could say I’m writing this purely as a researcher, analysing other people’s woes from a safe distance. Nope. I’m writing as someone knee-deep in rejection emails myself.

At this point, I want to crawl under my desk and go to sleep. The exhaustion is so complete. For the last 5 weeks or so I have had one form of professional rejection or another. So, how exactly do we bounce back when academia seems determined to chew us up and spit us out?

Here’s how I’m (attempting to) handle it. No glitter. No unicorns. Just practical steps — and a healthy dose of gallows humour — for getting back up, trying again, and not giving up – Ad Astra Per Aspera!

1. Stop Personalising the Systemic

Academia feels personal because we tie so much of our identity to our work. Rejection can feel like someone’s declared you not good enough as a human being.

But more often than not, it’s about:

- Too many applicants, too few slots

- Internal politics

- Budget cuts

- Strategic priorities we’ll never see coming

It’s not always about you. Sometimes it’s just the system being the system and that can be very frustrating to recognise. On one hand, it’s affirming that YOU are not being targeted for rejection, nor is YOUR idea. But then, on the other hand, you may feel powerless because this implies that you have very little control over it. Its like the AI generated image above – at first it makes sense, but the more you look at it, consider it, question it, the more it breaks your head! It can kick your confidence and break your spirit. It’s easy to say don’t let it, much harder to do. BUT, you can try to control the idea that it is all on you. Others participated in your attempt. No-one failed, it just didn’t make the cut – THIS TIME.

2. Run a Post-Mortem — But Ditch the Self-Flagellation

Treat every rejection like data:

- Ask for feedback if you can get it.

- Analyse the language for clues about fit, gaps, or politics.

- Compare your bid or application to successful examples.

It can be tempting to look for a villain; to pull the mask off the one who destroyed your dream. But in doing this, you run the risk of cackling and starting to shout about meddlesome kids when you tear the metaphorical werewolf mask from your head. Let’s be all Velma about this. Use the clues and cues to know why your bid didn’t make the cut. The best you can have is feedback (JINKIES – CLUES) which you can use to power forward. But — and this is crucial — don’t let it morph into a story about your worth. Keep it forensic, not emotional.

3. Control What You Can

Once you realise that you cannot control the whole process, you can then recognise that you can’t blame yourself for every outcome. You can’t control who sits on the panel or how many internal candidates they favour.

But you can control:

- Volume of applications. Keep firing off submissions. Small wins build momentum.

- Networking. Find out who’s influential in your field. Collaborate. Get known.

- Skills gaps. Plug them. New methods, new angles, new writing styles — keep evolving.

Sir Samuel Vimes of the Ankh Morpork City Watch habitually views the world according to crime. Big crimes and little crimes – Commander Vimes KNOWS that he can not control everyone, but he can recognise behaviour and learn from mistakes. Vimes does the job that is in front of him and learns. If you learn something, you haven’t failed.

4. Recalibrate Your Metrics

Academic careers aren’t linear. People vanish for years and resurface as department heads.

Measure your progress in broader terms:

- Papers written

- Grants submitted (not just won)

- Collaborations started

- Skills acquired

- Audiences reached

These all count. And they build toward bigger opportunities. Nearly 30 years ago, at the age of 11 I finally beat the “Facility” level in Goldeneye 64 on 00 Agent in 1:57 seconds. 8 seconds faster than time required. This was a big moment for 11-year-old me. I knew every inch of that level. To the point where today, I could map it out on a piece of paper. I know where every guard is, every pick up, every locked door. I also know that luck played a part. Dr Doak, an NPC which will be in one of 4 locations. To meet the time constraint he has to be in 1 of 2 of his locations. If he is at one of the other 2 locations, you will fail the mission.

In many ways – I think this is exactly the same here. Each play through told me a little more about which guards to subdue and which to avoid, where to the keycard, how to get a scientist to open a door for you etc. Each playthrough added experience, skill, and achievements until it all came together. Recognition of that made me want to try again, play it through one more time to achieve my goal.

5. Change the Narrative

It’s tempting to say, “I’m failing.”

Try this instead:

“This was a tough cycle. I’m working out my next angle.”

Not toxic positivity — just strategic narrative-building. You need to believe you’re moving forward, even when the system says “no.” I included the Doctor Who quote not only because it’s apt when discussing our “stories” and the framing within them, but also because of the current state of Doctor Who in general (at the time of writing). Doctor Who is on the decline (apparently), there is real fear that the public’s appetite for it has waned, with blame being spread on acting, writing, setting, and lack of originality. Every so often, I look at these episodes which are being smashed online and I think about the hundreds of people who were involved in their production. I think about the hard work built into each moment, from scripting to production to promotion. They are amazing. There are so many Nos in Who history. From Verity Lambert and Waris Hussein’s uphill battles to RTD and Stephen Moffat’s determination to return Who to screen for over a decade, to Chris Chibnall, Ncuti Gatwa and Jodie Whittaker, whose passion and limitless variety of imagination and performance have been continually lambasted despite their endurance. How must they all feel. To work so hard, and to watch it be brutalised and criticised. To see work that took months, years, be reduced to a pithy, scorn-filled social media quote or headline in seconds. How do they get through it?

Similar to academia, it seems they endure because they have too, and because they recognise the wins and celebrate their experiences. They say they learned from their role, that they loved being where they were, that they enjoyed it when they could. Its not about comparing or pulling down yourself, but seeing the value in your input and the work with those around you.

6. Look After Your Energy

Rejection fatigue is real. Here’s how to counterattack:

- Take a week off applications.

- Do something creative: write something funny, tinker with a hobby, help someone else.

- Move your body. Walk. Run. Punch a pillow. Whatever works.

- Talk to people who remind you you’re more than your CV.

In Back to the Future, a recurring theme is that the DeLorean is continually out of fuel, one way or another. In the first film, the time circuits need 1.21 gigawatts of electricity to work; in the third, it’s gasoline which is unavailable. (The second film doesn’t lend itself well to this analogy lol). The point is that in both cases ideas are tested and rejected as a ways to replicate the fuel required are depicted by montage and comedic scenes. UNTIL, a solution is found, usually after the narrative switches to a secondary plot for a while (Marty avoiding the incestuous advances of his teenage mother, Doc falling in love with a would be dead school teacher and therefore changes history, both characters continually terrorised by multiple versions of the school bully, Biff). Sometimes, you need to switch plot points and do something else. Do get back to 1985, but maybe enjoy the scenery in 1885, 1955, or 2015 first?

7. Remember: You’re Playing the Long Game

Academia moves at glacial speed. That doesn’t mean wait around. It means act while time passes.

Most success stories look like this:

- A period of relentless rejection.

- A sideways or unexpected opportunity pops up.

- Years of accumulated experience suddenly fit that opportunity perfectly.

This is the one that I struggle with the most, the Long Game. The long game implies that it will work out in the end. I really struggle to believe that. I’ve had a lot of endpoints in my life, and the idea that it will come good just doesn’t sit well. In the Ghostbusters, the original team are thrown out of their university with their grant money cut off, forcing them to look at a new way to make money – the result “The Ghostbusters”. However, these academics come to emergency services as a metaphor because they represent the truth that many academics ultimately find themselves seeking shelter in the private sector because academia can no longer support them. I want to see the Ghostbusters as an indication that you can end up in the right place at the right time, to allow you to make a difference. But, the analogy can be stretched to recognise how the story of the Ghostbusters is not one of success but one of sacrifice. These heroes gave everything they had, saved a city (twice), and yet it’s clear that decades later, they have been forgotten about. Each of them was squandering in their side hustle because the field had no place for them. This is my underlying fear when I get another rejection: that this is my future. To be on the outside forever, with each rejection eating away the time I have left until my luck runs out and I have nowhere to go with a skillset that no one needs.

Rejection doesn’t mean ‘no forever’ It can mean ‘not yet.’

Being rejected doesn’t mean you’re not good enough. It just means the slot you aimed at wasn’t the one that was yours. Yet. Keep swinging. Keep laughing at the absurdity of it all.

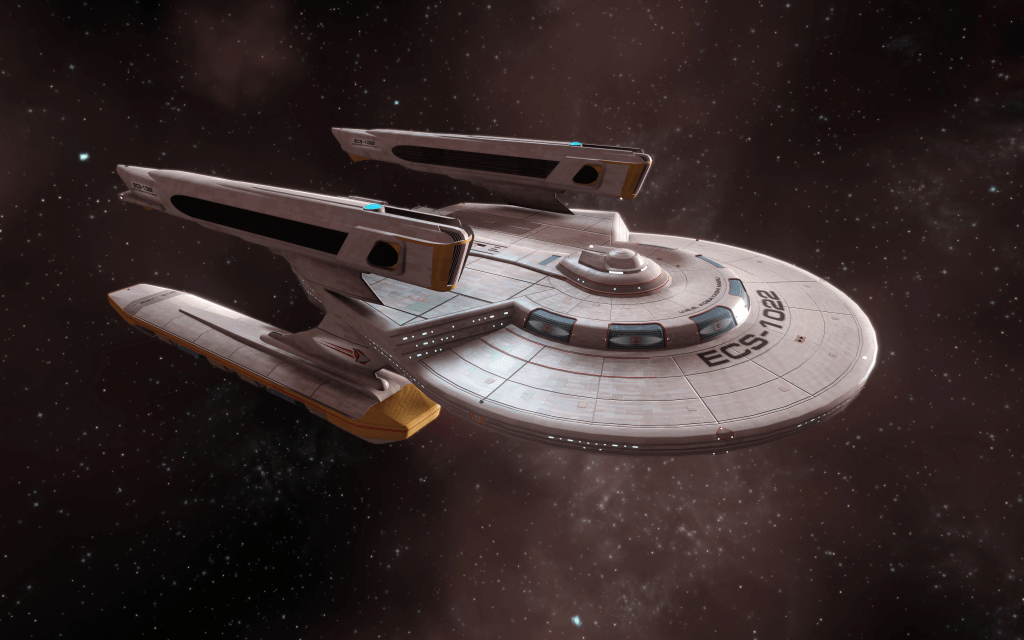

The picture above is of the fictional starship, the Kobayashi Maru, from Star Trek. The Kobayashi Maru is a test that all command cadets go through while at Starfleet Academy. It is a “No Win Scenario” designed to test the ability of the captain and crew under extreme pressure, and to remind all that there is not always a satisfactory resolution. The test taught endurance and the weight of decision-making. It taught the importance of relying on others and the ability to accept constructive criticism to improve. Most of all, it taught captains and crews how to accept inevitable failure and minimise its impact. With the exception of one renegade cadet, no one ever “beat” the test because that was the point of it. In essence, the only way to fail was to refuse to recognise that loss was part of life and that to survive, we have to adapt to it. By that framework, the only cadet to ever “fail” the test was Captain James T. Kirk.

When I’m sad or dejected, I turn to fiction for meaning, just as I have here. I know that a lot of these metaphors or analogies are all just stories and fictional, but from them I find comfort. These characters and their creators are very special to me. They have been my friends during times when I have had none, carers when no one cared. They have inspired and propelled me forward when I have hit a wall. Some may say that I have hid behind them, but they have helped me to realise that it is ok to hit the mat and try again. It’s ok, to struggle and admit it. It’s ok, to have a break. It’s ok to be broken. I’m human, and today I am sad, I’m exhausted, and I don’t want to do this anymore. I’m afraid and I’m defeated.

But I am also special. I am determined. I am passionate about what I do and what I believe in. I am worth investing in. And so are you. So yes, today is another NO, and yes there are lots more to come. But not always, not forever.

Celebrate when you can.

Refuel when you need to.

Remember you are not your work, no matter how closely aligned you are to it.

And when you are ready, look for me, look for all of us – willing you the strength to have another go,

Ad Astra Per Aspera,

Want to share your own rejection stories or vent? Drop me a message. Or come find me at the bar, where we’ll toast to our collective brilliance — and the utter chaos that is academia.

– Dr Simon H. Walker

Leave a comment