I am currently at the 4th IGPP Suicide Prevention Event in London, and as usual while the presentations are fantastic, the real discoveries are made in the chats next to the coffee machine. This has encouraged me to recycle an older piece I wrote about the issues of practical engagement with suicide prevention. This is one of the main questions about any discussion about suicide – how do we stop it from happening? One of the core issues is about responsibility? Who is responsible for preventing suicide, and how can this be managed. There are multiple research questions here but often examination of the impact of suicide, removes the practical element of prevention.

Suicide is a choice. Saying that can sound judgmental while it is not meant that way, particularly because is not my right to claim that suicide is a bad choice. Typically suicide is described as a release from pain, from being a ‘burden’, an escape from a negative situation. In my experience, both personal and through research, suicide is typically about change – change from one reality to a perceived better one, and recognition of the need for this change can feed into prevention strategies. My research focuses significantly on the potential to support individuals and identify a opportunities for suicide prevention through OH services and in work relationships. The workplace provides a unique opportunity for suicide risk recognition, even if the cause is not directly related to work. This is something that is being developed and requires further research and investigation.

Best Methods for Suicide Prevention: A Comprehensive Review

Suicide remains one of the most pressing public health challenges globally, with approximately 700,000 deaths annually according to the World Health Organization (WHO) (2021). However, suicide is preventable, and effective interventions can significantly reduce the risk of suicidal behaviors. Prevention strategies must be comprehensive and multi-faceted, addressing individual, community, and societal levels. There are several potential ways in which to reduce the risk of suicide, some focused on prohibiting suicidal action, some on mental health, and some on risk recognition; and each have their own issues and merits.

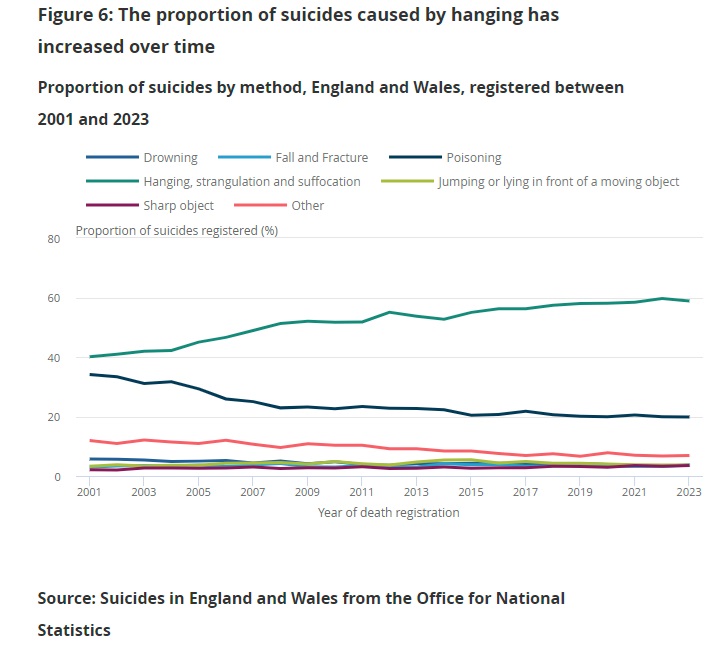

1. Restricting Access to Lethal Means

According to research one of the most effective approaches to reducing suicide is restricting access to means of suicide. According to Mann et al. (2005), reducing access to common means such as firearms, pesticides, and high structures can dramatically decrease suicide rates. A prominent example is the restriction of lethal pesticides in Sri Lanka, which resulted in a 70% reduction in suicide rates (Gunnell et al., 2007). Similarly, installing barriers on bridges and train platforms, and restricting access to firearms in high-risk populations, have shown significant declines in suicide incidents.

Key Evidence:

- Studies have consistently shown that reducing access to means reduces impulsive suicides, allowing individuals time to reconsider their actions or access help (Daigle, 2005).

Issues – However, removal of means can have the impact of forcing individuals to undertake suicide in different and often more unpleasant ways. In the UK, access to firearms or pharmaceuticals are limited, which means that often alternative suicidal action is sought. This can mean that individuals will choose ways that impact others (transport deaths, public deaths, falling, fire) or experiment with innovative methods of suicide involving illegal substances. Some of these methods can widen the time it takes for death to occur allowing for potential intervention. However, currently there is no concrete research to indicate that restriction of access to methods of suicide have a significant impact on suicidal action.

Source: Suicide Methods USA 2022

2. Public Awareness Campaigns and Media Guidelines

Educating the public about suicide, mental health, and available resources can raise awareness and reduce stigma, leading to earlier intervention. National campaigns such as “RUOK?” in Australia and “It’s Okay to Talk” in the UK have shown to increase help-seeking behaviors. However, public campaigns must be carefully designed. Pirkis et al. (2017) highlight that poorly handled media reporting on suicide can contribute to contagion effects, where vulnerable individuals may imitate the suicide method described (often referred to as the “Werther Effect”). Thus, media guidelines, such as those developed by the WHO and Samaritans, aim to promote responsible reporting and emphasize the positive impacts of seeking help.

Key Evidence:

- Responsible media reporting reduces suicide rates by mitigating contagion effects, while campaigns that increase mental health literacy improve help-seeking behaviors (Niederkrotenthaler et al., 2010).

Issues – Dazzi et al (2014) clarified that talking about suicide does not mean increased suicidal events. However, the power of language is potent and can be responsible for the negative perspectives of suicide. There is also a concern about detailed documentation about suicide being used as a blue-print for suicidal action.

3. Crisis Intervention and Suicide Hotlines

Crisis hotlines and intervention services provide immediate, accessible support for individuals in suicidal crisis. One of the most well-known services is the Samaritans in the UK and Ireland, which has provided confidential support to those in distress since 1953. A meta-analysis by Gould et al. (2013) shows that these services can reduce immediate distress and suicidality, especially when combined with follow-up interventions.

Recently, technological advances have expanded the scope of crisis interventions. Digital platforms like Shout in the UK offer text-based crisis support, catering to younger individuals who may be more comfortable seeking help via technology. Moreover, AI-driven algorithms have been implemented in social media platforms to detect signs of suicidality, alerting authorities for rapid intervention.

Key Evidence:

- Crisis intervention services have been shown to significantly reduce distress in suicidal individuals, with follow-up being crucial for preventing recurrent attempts (Mishara & Daigle, 2017).

Issue – These are the amongst the most effective first stage engagements for individual suicide recognition and prevention. However, many of them are maintained by individuals with limited training or additional support. Volunteers can be overloaded with mental health issues. The Samaritans is of course an exception as it is known for its diverse engagement to safe-guard their volunteers including Emotional De-briefing, Peer Support Networks, Ongoing Supervision Professional, Support Services Training in Resilience and Self-Care, Time Out and Flexible Scheduling Mental Health Resources, and Workshops Confidential Helpline for Volunteers Buddy Systems.

4. Training Gatekeepers and Frontline Workers

Gatekeeper training programs, such as Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) and Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training (ASIST), equip non-mental health professionals—such as teachers, police, and community leaders—with skills to identify and support individuals at risk of suicide. According to Isaac et al. (2009), these programs improve knowledge, attitudes, and referral behaviors among participants, increasing the likelihood that individuals at risk will be identified and connected with appropriate care.

In high-risk occupations, such as healthcare and military settings, specialized training is crucial. Studies, including my own research in occupational health, show that sectors like nursing, where suicidality is significantly higher (Milner et al., 2016), benefit from bespoke training that integrates occupational stress and mental health support (Cleary et al., 2012).

Key Evidence:

- Gatekeeper programs are proven to increase early identification and reduce suicide attempts through timely intervention, particularly in occupational and community settings (Gould et al., 2013).

Issue: Mental Health First Aid and appointment of Champions (numerous terms) brings with it the potential to relegate complex issues to an additional part of someone else’s role. Training for these roles is varied and in many cases the individual appointed can already have past mental health issues and/or become overwhelmed. Data on this is limited, however it is known that working in emotionally taxing environments, including roles like being a Mental Health First Aider, can pose mental health risks. Mental health professionals, including first aiders, are often encouraged to seek ongoing supervision, peer support, and mental health resources to help manage their own well-being(BioMed Central)(AFSP)(RAND Analysis). For those interested in the intersection of mental health support work and suicide prevention, it’s essential to recognize the emotional demands on those providing care, and prioritize self-care and professional support systems.

5. Psychological Therapies

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is widely recognized as one of the most effective psychological interventions for individuals experiencing suicidal ideation. Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), which focuses on emotional regulation, is particularly effective for individuals with borderline personality disorder (Linehan et al., 2006). A systematic review by Tarrier et al. (2008) found that individuals receiving CBT interventions were 50% less likely to attempt suicide than those receiving other forms of therapy.

Additionally, the use of brief, structured interventions such as the Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS) model, designed to directly address suicidal thoughts and behaviors, has demonstrated efficacy in reducing future suicide attempts (Jobes, 2016).

Key Evidence:

- Evidence strongly supports the effectiveness of psychological interventions, particularly CBT and DBT, in reducing suicidal ideation and behaviors in high-risk populations (Tarrier et al., 2008).

Issue: CBT & DBT are effective methods of suicidal prevention and mental health recovery. An issue here is about access and training for these elements. Occupational Health provides a potential support option for this however currently, less than 40% of British workers have access to OH, which could offer a range of focused services for suicide prevention and mental health engagement.

6. Follow-up Care After Suicide Attempts

One of the critical periods for suicide risk is immediately following a suicide attempt. Follow-up care, such as regular check-ins via phone or text, can reduce the risk of re-attempts. A study by Fleischmann et al. (2008) demonstrated that brief intervention and follow-up (BIC) reduced suicide deaths in patients who had previously attempted suicide.

Furthermore, “caring contacts” approaches—where healthcare providers send simple, non-demanding messages of support—have been shown to decrease suicidal behavior and feelings of isolation (Carter et al., 2017).

Key Evidence:

- Regular follow-up care, especially in the critical post-discharge period, has been shown to significantly reduce the likelihood of repeat attempts (Fleischmann et al., 2008).

Issue: Follow up care is essential particularly in the early stages of a suicidal action where an individual typically can feel guilt, failure, regret, anger, or embarrassment. However, this ongoing support often quickly diminishes due to cost and engagement opportunities. Additionally, individuals who attempt suicide or are impacted by an occurrence of suicide may not demonstrate an intent or attempt suicidal action months or years after the original event. Support at this level is limited to the NHS or private health care, and is typically over subscribed and highly pressured.

7. Addressing Socioeconomic Factors and Inequality

Suicide prevention efforts cannot solely focus on individual-level interventions. Suicide rates are disproportionately higher in populations experiencing socioeconomic deprivation, unemployment, and marginalization (O’Connor & Pirkis, 2016). Structural interventions, such as increasing access to employment, housing, and healthcare, play a critical role in reducing suicide risk. For instance, increased access to mental health services in lower-income areas has been linked to lower suicide rates (Reeves et al., 2015).

Key Evidence:

- Socioeconomic interventions that target unemployment, housing instability, and inequality are essential components of national suicide prevention strategies (O’Connor & Pirkis, 2016).

Issues: The biggest issue here is the often the absence of information and opportunity to recognize this issues before an event. This potentially opens up opportunities for better engagement at a OH level, working with supporting staff, HR departments, and Return to Work services.

Conclusion

The best methods of suicide prevention are those that employ a multi-layered approach, addressing risk factors at the individual, community, and societal levels. While restricting access to lethal means and providing immediate crisis intervention are crucial, longer-term strategies that include psychological therapies, follow-up care, gatekeeper training, and addressing socio-economic determinants are equally important. Through coordinated efforts across healthcare, communities, and governments, suicide can be prevented, and lives can be saved.

References

- Carter, G. L., Clover, K., Whyte, I. M., Dawson, A. H., & D’Este, C. (2017). Postcards from the EDge: 5-year outcomes of a randomised controlled trial for hospital-treated self-poisoning. British Journal of Psychiatry, 200(2), 121-126.

- Daigle, M. S. (2005). Suicide prevention through means restriction: Assessing the risk of substitution. Crisis, 26(4), 154-163.

- Fleischmann, A., Bertolote, J. M., Wasserman, D., et al. (2008). Effectiveness of brief intervention and contact for suicide attempters: A randomized controlled trial in five countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 86(9), 703-709.

- Gunnell, D., Eddleston, M., Phillips, M. R., & Konradsen, F. (2007). The global distribution of fatal pesticide self-poisoning: Systematic review. BMC Public Health, 7(1), 1-15.

- Isaac, M., Elias, B., Katz, L. Y., et al. (2009). Gatekeeper training as a preventive intervention for suicide: A systematic review. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 54(4), 260-268.

- Jobes, D. A. (2016). Managing Suicidal Risk: A Collaborative Approach. Guilford Publications.

- Mann, J. J., Apter, A., Bertolote, J., et al. (2005). Suicide prevention strategies: A systematic review. JAMA, 294(16), 2064-2074.

- Milner, A., Witt, K., Spittal, M. J., & LaMontagne, A. D. (2016). Suicide by occupation: Systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 209(2), 73-84.

- Pirkis, J., Blood, R. W., Beautrais, A., et al. (2017). Media guidelines on the reporting of suicide. Crisis, 28(3), 177-187.

.

Leave a comment