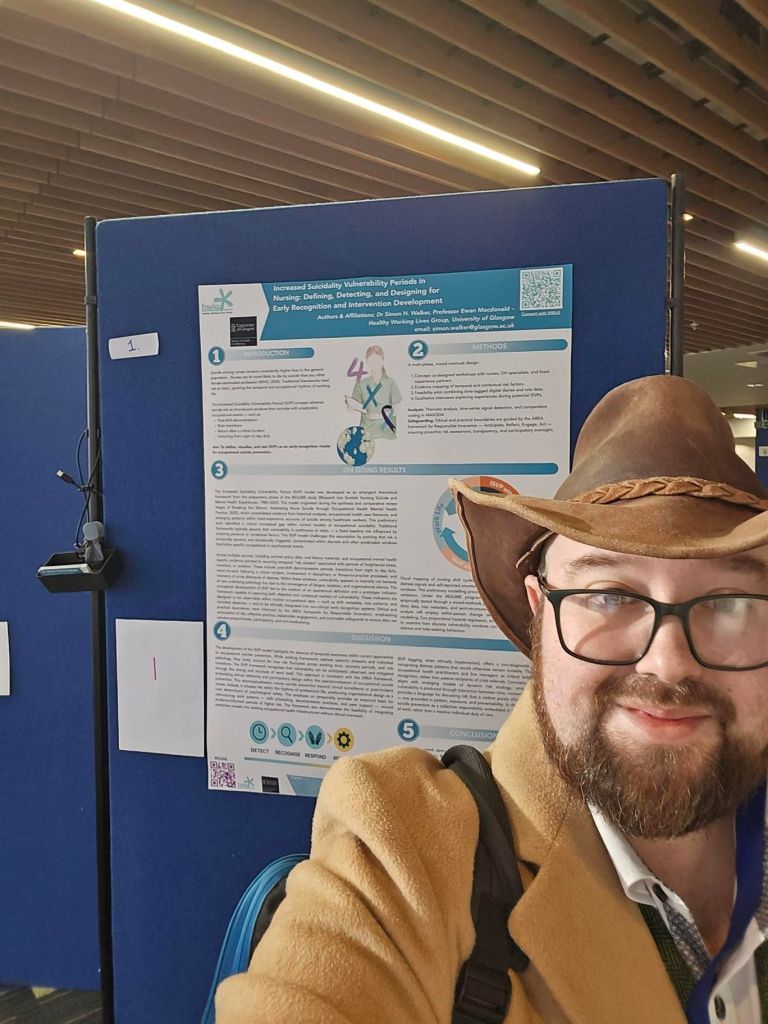

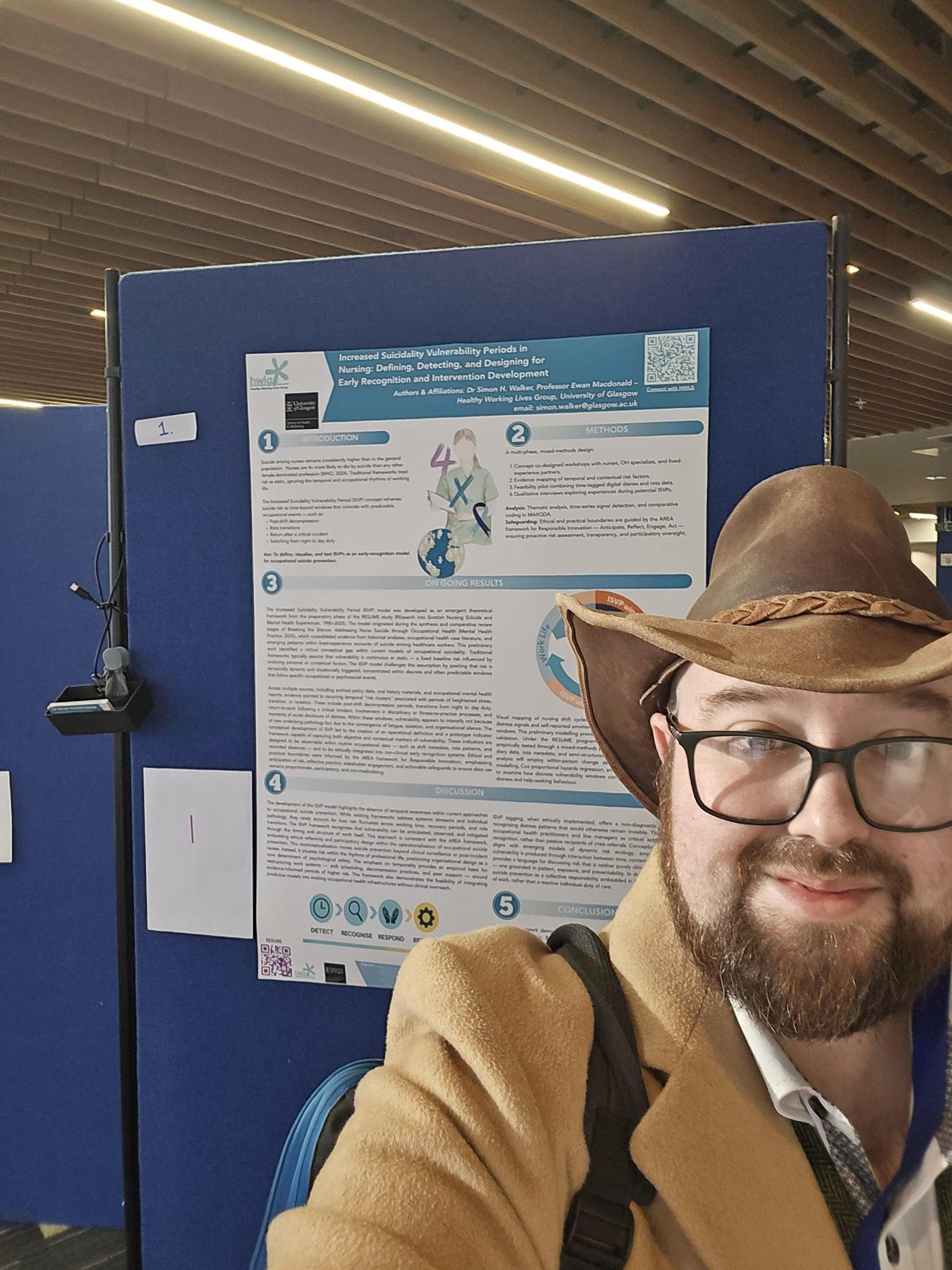

I am at the NHS Research Scotland Mental Health Network Annual Scientific Meeting hosted at the University of Strathclyde today, presenting a poster on our Nurse Suicide Prevention work and soon to be published ISVP model (Intensifed Suicidality Vulnerability Periods).

But of course, the best part of any conference is…well the coffee & catch up, BUT the next best is the talks and the last by Professor Alan Simpson (Kings) on patient surveillance really got my head spinning.

Simpson’s excellent talk discussed how the integration of surveillance technologies into healthcare has accelerated in recent years, particularly within mental health and acute inpatient settings. These systems—ranging from closed-circuit television (CCTV) and wearable sensors to body-worn cameras and vision-based patient monitoring—apparently promise to enhance safety, efficiency, and clinical oversight. Yet, as Simpson and his team demonstrated, the evidence supporting these claims remains strikingly thin.

The 2024 systematic review by Griffiths et al. in BMC Medicine examined the use and impact of surveillance-based technology initiatives in inpatient and acute mental health settings. The review synthesised 32 studies covering CCTV, GPS monitoring, wearable sensors, and other “smart” surveillance tools. Despite the optimistic framing of many initiatives, half of the studies were rated low quality, and only a third provided methodologically robust data.

The findings were sobering. Across diverse technologies, clear evidence of benefit was inconsistent or absent. Reported reductions in incidents of self-harm or aggression were often anecdotal or confounded by concurrent changes in staffing or ward policies. The promise of cost-effectiveness was similarly overstated—few studies accounted for the ongoing costs of data management, maintenance, or ethical governance. What emerged most strongly were contradictory human experiences. Patients and staff described both reassurance and distress: some reported feeling safer, others reported heightened anxiety, loss of privacy, and erosion of trust. For individuals experiencing psychosis, paranoia, or trauma, the experience of constant observation could replicate or intensify existing fears. These are not trivial side effects; they cut to the heart of therapeutic relationships and the ethics of care.

From a policy standpoint, the study exposes a familiar pattern: technological adoption has outpaced evidence and ethical deliberation. Surveillance systems are being deployed as instruments of risk management in environments already characterised by asymmetries of power. The assumption that “more monitoring equals more safety” ignores the relational and contextual dimensions of care that underpin patient wellbeing. It is at this point that our work on suicide prevention steps back into the ring because a large part of our focus on suicide prevention is associated with surveying or at least allowing self surveillance in tandem with prevention support tools.

There are legitimate reasons to explore digital monitoring where it may reduce physical restraints, improve response times, or support observation in high-risk environments. But these interventions require independent evaluation, transparency, and co-production with lived-experience researchers. The Griffiths review rightly foregrounds this: without meaningful participation of those being watched, surveillance becomes not a safety tool but a mirror of institutional anxiety.

We live in a society where technology allows for the tracking of every step, breath, and action we take. Within my research having the ability to track mood, actions, and thoughts is incredible as theoretically, particularly if combined with physical manifestations of mental health distress, surveillance would allow for nearly total suicide prevention. But at what cost? Is creating a virtual panopticon worth the loss of agency and privacy? As Foucault warned in Discipline and Punish, the modern surveillance apparatus operates less through direct coercion than through the internalisation of observation. In healthcare, this creates a new kind of panopticism: patients self-regulate under the gaze of unseen watchers, and clinicians perform for the lens. Safety becomes spectacle, and care risks collapsing into compliance.

Therefore, healthcare surveillance sits at an ethical crossroads. It reflects the tension between care and control, observation and intrusion. As the NHS continues to invest in “smart” wards and predictive safety technologies, the question is not whether these tools can see more—but whether they help us understand more, and care better, and are they worth the overall financial, societal, and liberty costs incurred?

Leave a comment